Welcome to BDI Briefs! In today’s episode, we delve into an important topic that affects many of us living with diabetes – the distinction between diabetes distress and depression. Join me as we unravel the complexities and shed light on the emotional challenges associated with diabetes.

For years, it has been widely believed that those of us with diabetes are at a significantly higher risk of experiencing depression. However, recent studies have challenged this long-held belief and revealed a different perspective. I, for one, am glad to hear this news.

Dr. Bill Polonsky, President of the Behavioral Diabetes Institute, and Dr. Susan Guzman, Director of Clinical Education at the Behavioral Diabetes Institute, have discovered that while the rates of depression among people with diabetes are not as high as initially believed, the prevalence of something known as diabetes distress is much more significant.

One differentiating factor is the nature of these challenges. Depression tends to have a more constant presence, affecting individuals most of the day and across many, if not all, areas of life in general. Diabetes distress, on the other hand, is persistent but directly related to the stressors surrounding diabetes. For example, identifying statements like “I’m a failure, everything is hopeless” suggests depression, whereas “I’m failing at diabetes, my efforts are hopeless” may indicate diabetes distress.

One of the key takeaways from Dr. Polonsky and Dr. Guzman’s research is the importance of providing the appropriate support and intervention for individuals experiencing these emotional challenges. While both depression and diabetes distress are treatable, the treatments differ significantly. Offering an antidepressant to someone experiencing diabetes distress may have little impact, as the emotional struggles are related to the specific stressors of diabetes itself. Addressing these challenges requires personalized, tailored conversations and support to help individuals navigate the complexities of managing their condition.

The American Diabetes Association has created the Mental Health Registry. This registry allows people to find diabetes-knowledgeable mental health professionals in their area. By connecting individuals with professionals who understand the unique challenges of living with diabetes, this resource helps ensure that the right help reaches those who need it most.

In conclusion, it is essential to differentiate between diabetes distress and depression to provide people with the correct support and intervention. While depression rates among people with diabetes are not as high as previously believed, diabetes distress is remarkably prevalent. Recognizing the distinction between these two emotional challenges empowers healthcare professionals and individuals alike to manage their emotional well-being more effectively.

You already know that living with diabetes is a continuous journey, and it is normal to struggle emotionally along the way. But by understanding the difference between diabetes distress and depression, we can take the right steps toward improving our emotional well-being and living well with diabetes.

Detailed show notes and transcript

[00:00:07] Scott K. Johnson: Welcome to BDI Briefs. This is another exciting installment where we take a brief look at important issues about the emotional side of diabetes. Thanks for joining us today. I’m here with Dr. Bill Polonsky, President of the Behavioral Diabetes Institute, and Dr. Susan Guzman, Director of Clinical Education at the Behavioral Diabetes Institute.

Both are world-renowned diabetes psychologists who do so much for everyone living with and working in diabetes. My name is Scott Johnson. I’ve lived with diabetes for over 40 years, and I’ve been active in the diabetes social media space and industry for a long time. Today, we are going to be talking about diabetes distress versus depression.

I’ve always heard that people with diabetes are at increased risk of living with depression as well. I think we need to unravel that a little bit because we’ve learned some over the past couple of decades or so, right? So with that, maybe I’ll throw it over to you, Bill, to get us started pulling on that yarn a bit.

[00:01:18] Dr. Bill Polonsky: thanks a lot, Scott, and I’m really glad we get to talk about this. It’s actually one of Susan’s and my favorite conversations because we’ve been very concerned about this. We know if you are a healthcare professional working in the field of diabetes or if you’re a person living every day with diabetes, you may have heard that you’re at elevated risk for running into a serious problem with depression.

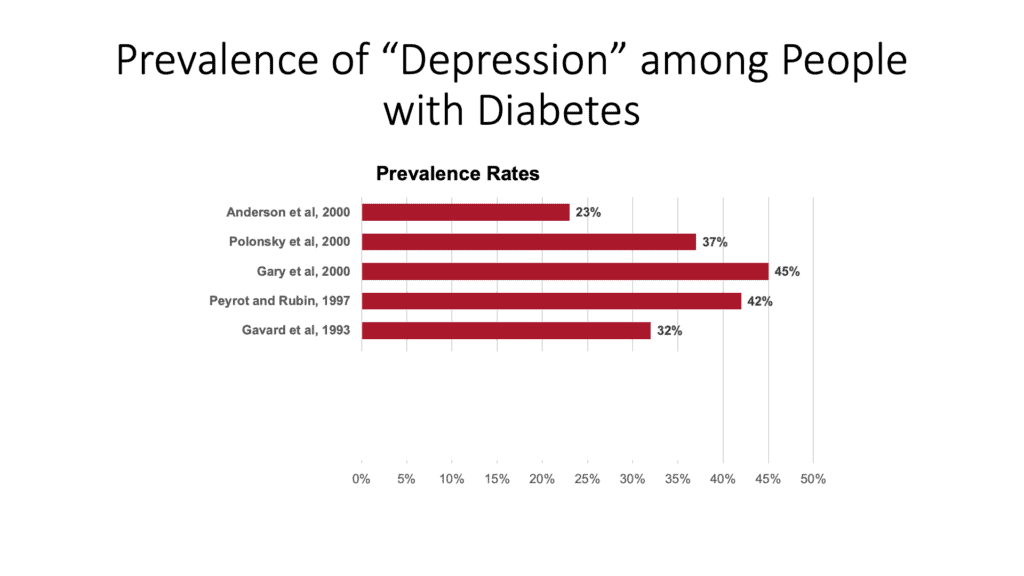

And that’s based on lots and lots of studies that were conducted in the 2000s. And on this very first slide, you can see some of those studies right here. When looking at those studies altogether, what we concluded from this is, wow, you can see that at least a third, maybe half, of people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes are struggling with significant depression.

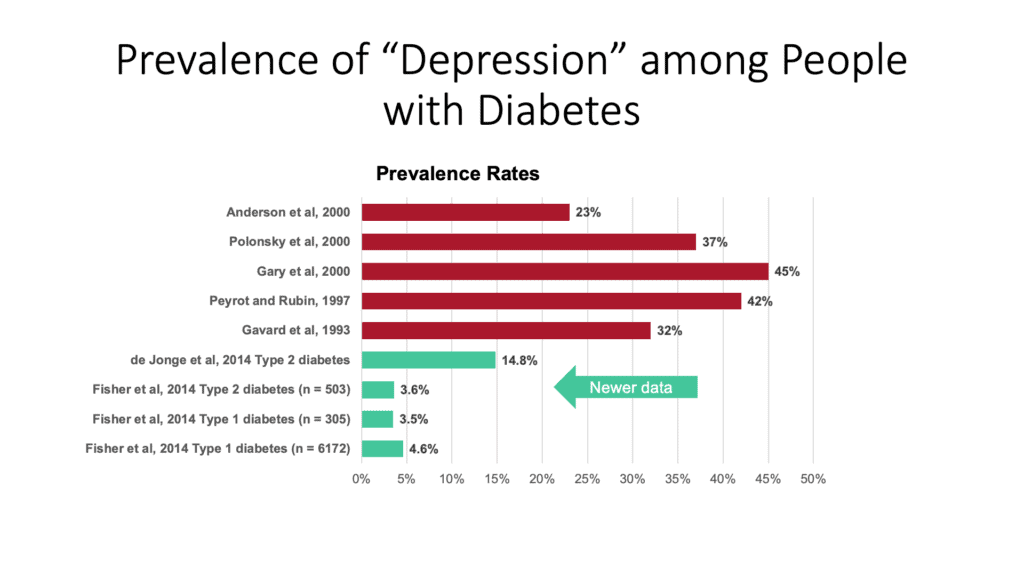

And also, we know from this same series of studies that what is suggested is that people with diabetes are at double or triple the risk of actually running into a really serious problem with depression compared to people who don’t have diabetes. But there is, as it turns out, more recent data helps us understand there’s something wrong with these studies.

So, as you can see now in the green part of the slide at the bottom, our newest data tells us something actually very different. In fact, there’s more than just that. Four studies are presented here. There’ve been others that I’ve had the chance to be involved in. Some of them, where we know the actual rate of running into a serious problem with depression is not 30, 40, 50%, but it might be 3, 4, 5, 6, maybe 8%, something like that could be even a little higher.

The data suggests that they may not be so different than people who don’t have diabetes, which is shockingly different from what we have said for years and years. So, I don’t mean to say that depression isn’t a big problem, and the combination of depression with diabetes is a really bad mix, right?

But the point is what we’ve learned is that the actual rates of depression are not nearly as high as we thought. And they’re not actually that different from people who don’t have diabetes. Now, here’s the funny thing, and this really relates to why we’re talking about this. Having said all that, I’m going to say something confusing.

But if we look at the most common screening questionnaire that we use to try and look for depression, it’s called the PHQ 9; what we know is that people with diabetes, type 1 and type 2, tend to score higher than people who don’t have diabetes. Now, wait a minute. They score higher. Doesn’t that mean they’re more depressed?

It turns out, at least when you do careful, structured interviews, it turns out that’s not true. These questionnaires to score high on a PHQ 9 are picking up something that’s going on with lots of people with diabetes. But in many cases, it’s not depression. And what it is, we call diabetes distress.

Now, we’ve done research regarding diabetes distress and the emotional side of living with diabetes. How it is that people can feel hopeless, discouraged, fed up, and overwhelmed. We’ve been doing this research for more than 30 years, and we now understand how common elevated levels of diabetes distress are, which you will see on this next slide.

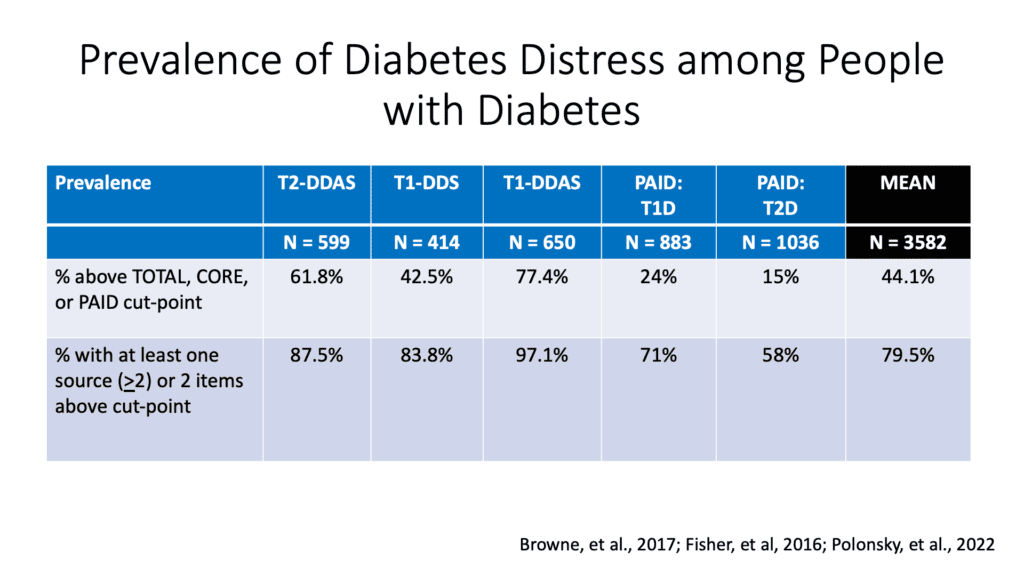

And what we’ve learned, looking at all the different ways we can measure it. And there are different scales that look just for people with type 2 diabetes and type 1 diabetes. This was a study, this was a presentation from our colleague Larry Fisher, who we’ve done much of this work with, is that what we see is that elevated diabetes stress is in fact way common for both people with type 1 and type 2 diabetes.

You can see it way over there on the right, on that first row. We estimate it’s about 44%. But again, depending on the questionnaire, it may be quite a bit higher. By the way, in that second row, we look at people who score high in one particular element of diabetes distress. Because many of these scales have different, what we call sources or subscales.

And there we see the numbers are even crazier higher. As you can see, the mean over there on the far right is 79. 5 percent. Which basically means something that is probably going to be obvious to many of you. Which is, if you have diabetes, type 1 or type 2, the odds are good something’s driving you crazy about living with this disease.

So why this is important is we think this is why people score high on that PHQ 9. So it turns out that depression rates are kind of low, and diabetes distress rates are, in fact, really high. We want to make that distinction, and we think it’s a very important distinction, for one critical reason, which is that as bad as depression is, As bad as actually elevated levels of diabetes distress are, the solutions, the treatments are very different.

If someone is fed up with their diabetes, giving them some, giving them antidepressant medication will accomplish very little. You have to actually talk to folks and help them address things that they’re struggling with and are driving them nuts. So, we want to think about the important distinction between depression and the idea of diabetes distress.

And I’m going to turn it over to Susan, who will walk through a little bit about how those things look different and how we understand how different they are. Susan, go for it.

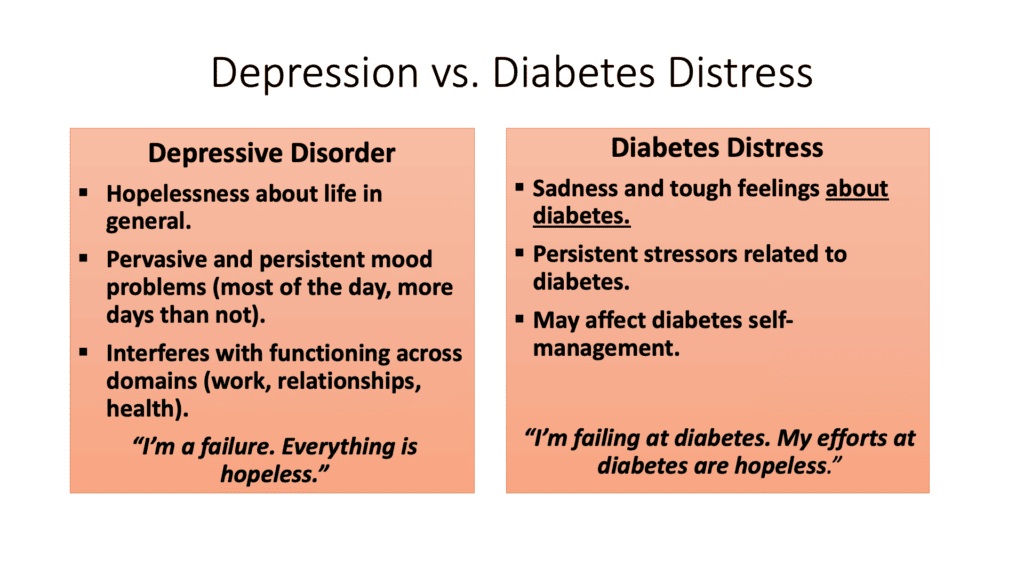

[00:06:59] Dr. Susan Guzman: Okay, so when I’m thinking about depression, I want to remember that this is a diagnosis. It’s a serious medical condition. And when I’m thinking about diabetes distress, it’s important to have a conversation about it, but the intervention is very different. So when I’m having a conversation to try and tease this apart with someone that I’m meeting for the first time, I’m really listening for the following things to tease them apart. So that’s what this slide reflects.

So, with depression, there’s more of a hopelessness about life in general. Whereas with diabetes distress, you’re really talking about the tough thoughts, worries, and concerns about diabetes. And with depression, you’re really looking for a more pervasive and persistent problem with mood.

In other words, it lasts most of the day and more days than not. With diabetes distress, we know that it’s persistent but related to the stressors related to diabetes. With depression, it really interferes with a wide range of functioning across domains such as work, relationships, and health. The kind of things you listen for are statements like, I’m a failure, everything is hopeless.

Whereas with diabetes distress, you may hear, I’m failing at diabetes, or my efforts at diabetes are hopeless. And both things can interfere with diabetes – or not. Sometimes, that can be a little tricky, too.

I think that sometimes we think that if somebody has their numbers at target, they probably don’t have either depression or diabetes distress. And the only way we can know is to ask.

[00:08:43] Dr. Bill Polonsky: That’s a really good point. One of the reasons why this is important and why it can be confusing is because these two problems overlap. As you can see from the things that are on this slide and what Susan was just talking about, there are some similarities here.

One of the things that depression and diabetes distress share is feeling out of control. With depression, it can be feeling out of control about life. With diabetes distress, it’s feeling out of control about diabetes, which is why we can often see this overlap when we’re talking to folks, in terms of what, if you’re a person with diabetes, you may be feeling sometimes.

And it’s why our funny questionnaires often don’t distinguish between them very well unless we ask. But the bottom line is we just want to highlight that what we typically used to call depression all the time, in many cases, isn’t depression. It really is diabetes distress. That depression and the rates of depression are much lower than we ever thought they were.

And what we’re starting to understand more and more about diabetes distress is the rates are much higher than we initially realized. This is very important so that if you’re a healthcare provider, the next time you run into someone who’s looking down and doesn’t want to talk to you, it looks like they might be feeling overwhelmed.

You don’t have to assume they have some terrible depressive disorder, even if they, by the way, fill out that PHQ 9. It is perhaps just as likely, if not more so that they’re really feeling like they’re failing and feeling hopeless about their diabetes, just like Susan was saying. Again, it’s important to be able to discriminate, though, so we can talk about providing people the right kind of help.

I don’t know. Susan, what do you think? Do you have other thoughts about this, or where do you want to go with this?

[00:10:38] Dr. Susan Guzman: I’m interested in hearing what Scott has to say before I have a last thought.

[00:10:44] Dr. Bill Polonsky: Good point.

[00:10:46] Scott K. Johnson: First of all, I’m very relieved to hear that. Just because I have diabetes, I am not necessarily automatically at this higher increased risk of depression. That, I feel, takes a load off my shoulders. Second, it also feels like it makes a lot of sense that many of us living with diabetes do deal with a lot of diabetes distress because it frankly takes a lot of work to live with diabetes.

The third thing that comes to mind is if I’m dealing with diabetes distress and I’m not getting the right help for that, I’m going to feel like a failure there as well, which just feeds into this negative cycle of feeling hopeless and fail, failing at everything I’m trying.

So I really appreciate the importance of distinguishing between the two so that the right help can be given.

[00:11:45] Dr. Susan Guzman: And the right help can get to the right person by helping make this distinct distinction. So that when we know that the person is distressed, we don’t offer them, for example, an antidepressant. And what we know is that both really respond to intervention. Both depression and diabetes distress are very treatable.

[00:12:09] Dr. Bill Polonsky: if you’re a person with diabetes and you’re feeling like you want to deal with some of these issues, one of the things that you might like to know about is the American Diabetes Association’s Mental Health Registry.

What’s nice about that is you can go to that website, which is on the diabetes.org website, and again look for the Mental Health Registry. You can put in your zip code, and it will tell you about diabetes-knowledgeable mental health professionals in your area. Of course, if you’re here in sunny San Diego, where Susan and I are, you can see us as well. The Mental Health Registry, which is still relatively new, allows anybody anywhere in the U.S. to hopefully find people in your area who may be able to provide you with the kind of help and support you need who are also knowledgeable about diabetes. And boy, that didn’t use to be true that even was possible or existed. So we’re delighted about that.

I’m not sure we need to say anything else about this.

We could go on for days and talk more about how important this is and how living with diabetes distress can make it harder for people to manage diabetes effectively. As Scott mentioned, it’s remarkable that not literally 100 percent of people with diabetes don’t struggle with diabetes distress every day, given that you’re dealing with this condition that you have to think about all the time.

And where it’s so easy to feel like you’re failing and it’s so driven by numbers and often difficult and problematic relationships with health care providers and dealing with the costs of your medications and technology as well. So it’s very understandable that it is so very common. And if you need some help, I hope you’ll reach out to get the help that you need rather than having to struggle.

Scott, I’m going to send this back to you. I hope this has been useful for everyone. And I’m really glad that you and I and Susan are here to be able to talk about this.

[00:14:05] Scott K. Johnson: Likewise, thank you. I’m so thankful for the work that all of you have done in this space, and my thanks go out to Dr. Fisher and all of the other wonderful colleagues you have worked with over the years.

I think this is a really important piece of living well with diabetes, and maybe in one of our future episodes, we’ll dive a little deeper into what we can do about diabetes distress.

We don’t have time to go into that today, but I think that there’s a lot of interest there as well.

Big thanks to everyone out there watching, and tune in again for our next episode coming at you very soon. Thank you!