Welcome to another episode of BDI Briefs! Our aim with BDI Briefs is to take a brief look at important issues about the emotional side of diabetes.

In this short discussion, Scott, Bill, and Susan explore problematic medication taking and what you can do about it. You may be surprised by some insights – I know I was!

Enjoy! And please let us know what you think and what you’d like to hear more about.

And remember to subscribe to BDI’s YouTube channel!

Detailed show notes and transcript

Scott Johnson: Welcome to BDI Briefs. We’re here with another exciting episode where we take a brief look at important issues about the emotional side of diabetes. Thanks for joining us today.

I’m here with Dr. Bill Polonsky, President of the Behavioral Diabetes Institute, and Dr. Susan Guzman, Director of Clinical Education at the Behavioral Diabetes Institute. Both are world-renowned diabetes psychologists and two of my favorite people around.

My name is Scott Johnson. I’ve lived with diabetes for over 40 years and have been active in the diabetes social media space and industry for a long time. And with introductions out of the way, Bill, what are we looking at today?

Bill Polonsky: Thanks, Scott. Well, we all want to talk about something that’s, I think, pretty important, which we call problematic medication taking.

In the old days, we used to use words like medication compliance and medication adherence. But my colleague Susan has taught me not to use those terms, although I still fall back on it. It’s just an old habit when we think about it as the issue of medication taking.

To get us started, I want to tell you something about what we know about medications in the treatment of diabetes, whether it’s oral medications, whether it’s injectable medications. We know there are a lot of choices. In fact, over the past decade or so, there’s been an explosion in the number of medications available for people with diabetes.

Bill Polonsky: This has been good news because these new medications often are remarkably effective. And yet what’s been disappointing about that is that if you looked at glucose control in large populations, look at A1C levels in people in the United States, over the past couple decades, really hasn’t changed much.

Bill Polonsky: So we have this very strange, seemingly odd problem where we have these better medications, way more choices, way more options available, and yet not seeing much of an impact across this country in terms of people achieving better glucose outcomes.

Of course, one of the major reasons is that medications don’t work well if people aren’t taking them.

Bill Polonsky: And that’s why I want to discuss this topic today.

So I want to set the stage, and then we’ll all chat about what the real issues are, and we’ll talk about what some of the real solutions are.

And I hope this is valuable for those of you who are healthcare providers and those who are living every day with diabetes, whether it’s type 1 or type 2.

So certainly, we aren’t the first to think about this issue and recognize that there’s a big problem. I’m not going to spend a lot of time reviewing all the data to show that a large, large percentage of people with diabetes over the course of, say, the first year after they start a medication simply aren’t taking it within three, six, or 12 months afterward. And there’s been lots of efforts to understand this and to figure out what to do.

Bill Polonsky: And what we know from studies that have looked at interventions, they look at, well, simple interventions like this, like, well, what if healthcare providers provide people with written instructions about exactly how to take these? Or provide them with what we call stimulus control efforts. And that sounds fancy, but it means like, “Hey, why don’t you leave your pills next to your toothbrush or the coffee pot?” It means involving loved ones, family members, and friends or packaging medications in little pill boxes, blister packs, or some other way. And in fact, hundreds of other kinds of strategies have been used. And when we look across studies that look at how effective those are, there was a recent review, well not recent, actually from 2017, that reviewed more than 700 of these very well done, what are called randomized control interventions.

They found that there was an effect, but it wasn’t much of an effect. What we call an effect size suggests it was a small effect. And the conclusion from this large, large review of all these different studies was, well, not only do we have this modest effect, but the bottom line is, well, as they said very politely, much room remains for improvement.

Bill Polonsky: This mostly just means our interventions to try and help people to be more successful in taking their medications over time didn’t really work that well. And we think we understand what the reason is. We think we understand what’s missing.

Bill Polonsky: What’s missing is if you look across the vast majority of our interventions that are typically used every day by many healthcare providers like those of you listening and watching us right now, most of those interventions are focusing on the idea that there’s a behavioral problem and one behavioral problem in particular, and that’s forgetfulness.

Bill Polonsky: It’s forgetfulness that’s the main reason why people are struggling with their medications. Actually, that’s often what people tell us. We look for interventions that try to deal with forgetfulness. Well, how about if I call you every few hours or give you a little app that will remind you or give you a timer or put it on a special pill box or you put it next to your coffee pot, things like that. It doesn’t work very well. And we think the reason is that the problem for so many people isn’t forgetfulness; it’s something else.

And to explain what that is, I wanna turn to this amazing commentary written in the New England Journal of Medicine. and it came from a cardiologist named Lisa Rosenbaum.

Bill Polonsky: I just want to read you a small part of what she wrote. Remember, she’s thinking about not diabetes, in particular, she’s looking at cardiac conditions and cardiovascular disease complications. And here’s what she says:

“It’s our job to help patients live as long as possible free of CVD complications. And although most patients share that goal, we don’t always see the same pathways to get there. I want to believe that if patients knew what I know, they would take their medicine. But what I’ve learned is that if I felt what they feel, I’d understand why they don’t.” — Lisa Rosenbaum, M.D.

In other words, people are acting rationally. We have to look at people’s attitudes and behaviors and their life perspectives on diabetes, pills, and medications.

It isn’t just forgetfulness. It’s patients’ understandable beliefs that we must respectfully understand better, listen to, and address.

And so some of those attitudes and beliefs that are important, number one, what we call perceived treatment inefficacy, which is a fancy way of talking about something that I’m sure is pretty obvious to you.

Bill Polonsky: That when you’re asking someone to take on a new, should be positive health behavior, like taking a medication every day, or like this woman going on a new diet, if you’re not pretty quickly seeing some tangible evidence that what you’re doing is accomplishing something, odds are pretty good you’re not gonna stick with it for very long.

But that’s a big issue, especially when you’re dealing with a relatively invisible disease like diabetes. Take your metformin every day. What’s the effect over the next couple months? Well, if you don’t look at your blood sugars, probably not much. You’re not going to notice anything because high blood sugars don’t actually hurt.

Another important issue is, well, you know all this. Medications, insulin, other injectables, they can be expensive.

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit. Ut elit tellus, luctus nec ullamcorper mattis, pulvinar dapibus leo.

Bill Polonsky: And if you can’t afford your medications… That’s a pretty good reason why medication taking can be a problem. We’ll talk about that.

We also know that many people actually hold some significant suspicions about medications.

Bill Polonsky: So maybe this stuff actually isn’t so good for me. People worry that maybe if I take those pills or I take those other medications, maybe that’s going to actually hurt me. I’ve heard about really dangerous side effects. And sometimes, it might be right.

But we have to be able to talk about that with folks. So those suspicions about medications are also a very sizable concern for many of the people I see every day. Actually, most of my family members feel this way, often suspicious about medications as well.

Oftentimes, when we think about why that might be true, it’s because of things they read and see daily.

Bill Polonsky: Perhaps you’ve seen ads or commercials like this. “Have you ever taken any of the following medications? If so, please call us. We can help you to make some money because we know how harmful and terrible these things are.”

Well, there are side effects to almost all of our medications, but really? Is that the only reason why we shouldn’t be taking them? Of course not.

Bill Polonsky: And isn’t it strange that so many people are quite happy to take vitamins and minerals and supplements, which by the way, there’s actually much less evidence in almost all cases that these are either good for you or not harmful, but yet there is this halo around vitamins and minerals because it’s this idea that well this is, this is a positive, this is a good thing for me. Whereas prescribed medications, I better be careful about that.

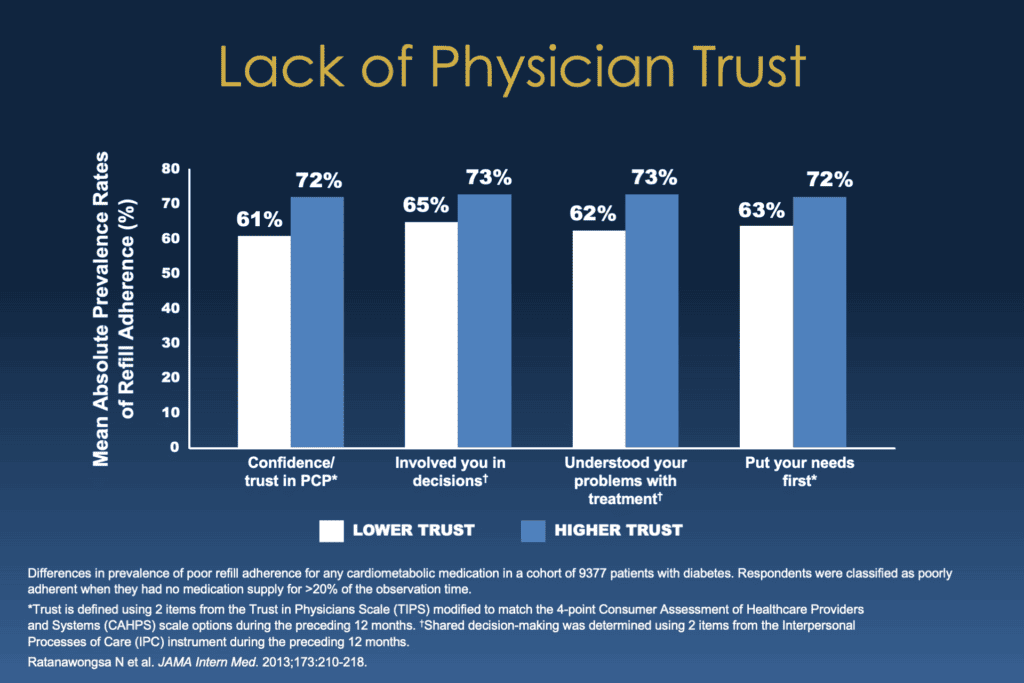

And finally, the last point about this is we know that another big driver of medication taking is a degree to which the person who has prescribed those medications for you is someone who you actually trust or don’t trust.

Bill Polonsky: And what you see on the screen here is from a study from the University of California at San Francisco where they simply looked at that. And what they found is those people who reported greater confidence and trust in their physician, those people who had greater trust are in the blue columns, were more likely to be taking their medications regularly than those people who had less confidence and trust.

You can see across the screen how that works. People who felt like their doctor involved them in decisions, understood their problems, put their needs first, all those things are related to doing a better job with one’s medications over the course of time.

And that should be obvious; it’s true for any of us. You trust your doctor, you trust the person who’s recommending these meds, who’s telling you that, yeah, there might be side effects, but I’m pretty sure the positives outweigh the negatives, you’re more likely to go along with that.

So it’s just this recognition that these things, how our patients think about their medications, are important. And if they’re having trouble problematically with taking their meds, it’s not because they forgot or they’re bad people or in denial, having ways of thinking about their meds that we want to listen to and be respectful of and perhaps try to address, which we’ll get to in a minute.

But let me stop. I’ve talked way too long. Susan, Scott, chime in. What do you think about all this?

Scott Johnson: I’m going to plead guilty to thinking that forgetfulness was a primary reason for people not taking their medicines. I think this sheds a whole new light on the reasons behind why people aren’t taking their medicines more. And I can see the behaviors of close loved ones in some of these descriptions. So it’s very enlightening.

Bill Polonsky:

Susan, what do you want to chime in? I know you and I have been studying this stuff for a long time.

Susan Guzman: Yeah, and related to this study on the lack of physician trust, when you dig a little deeper into this study, one of the really interesting things was they looked at cardiometabolic medicine. So that included not only diabetes medication but blood pressure medication and cholesterol medication. And guess which one had the biggest relationship to trust? It wasn’t even across the board.

And I’m challenging you to think about that because there’s one particular area in there that we do a lot of negotiating with. And people, the biggest effects on trust were the diabetes medication, the glucose-lowering medication, not the blood pressure medication, not the cholesterol medication. It was the biggest effect.

I mean, there was an effect, but the biggest effect was for glucose-lowering medication. That’s one that people tend to negotiate with more. Like, do I really need that? You know, I hear if I lose weight, if maybe those medications, in particular, mean something bad about me. Maybe that means I’ve failed, and maybe that means my diabetes is getting worse, and maybe that means I’m getting sicker. Or people don’t necessarily do that with other chronic health conditions, like high cholesterol and high blood pressure.

Bill: Polonsky: Well, they do. They just may not do it as frequently or as often.

Susan Guzman: Right.

Bill Polonsky:

Before we go on, I want to respond to something that Scott said, which is, because I want to make sure I say this correctly, forgetfulness is a big issue for many folks. It’s certainly in certain subsets of the population, especially if you have diabetes and you’ve gotten pretty old, and you’re starting to lose your ability to have awesome… If you’re not thinking particularly well, you’re losing your memory.

Yeah, forgetfulness can be a big issue. For people who are living really profound, chaotic lives, they don’t have a lot of structure in their lives. Again, forgetfulness can be a big issue. Our whole point is that we want to emphasize it’s not the only one. And if we only address that, we’re missing a lot.

Susan Guzman: And one more thing about forgetfulness is that it’s an easy thing to explain for behavior, you know, and it’s a good save face like, “Oh, I forgot.” Rather than “I don’t trust you, doctor.”

Bill Polonsky: Yeah, that’s a really good point.

All right, so I know our time is limited, so let’s talk about the most important part of this, which is what do you do about this? Especially if you’re a caring healthcare provider and you’re running into lots of folks who are really struggling with taking their medications.

Bill Polonsky: And again, we have overwhelming evidence if we can help our patients take their medications more reliably and regularly, we can help them to get to a safer place with their diabetes and live a long and healthy life.

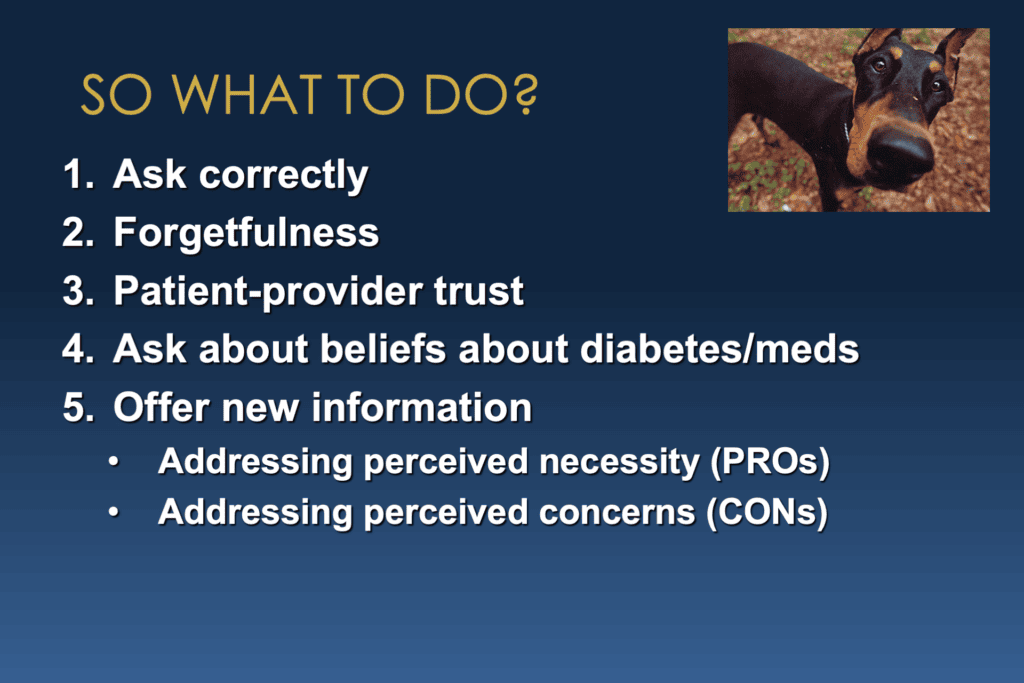

So I have a very short list of things we know really matters. I wanted to walk through this with you guys. And there are just five. So I want to start with the first one.

Bill Polonsky: The most important one is this. You need to ask your patients about this. That’s what’s really critical.

We find so often that healthcare providers will tell us, Susan, you hear this all the time as well, you know, “I’ve heard about this problem with medication taking, but nope, not really with my patients.” And oftentimes, that’s because this is how we ask. “Hey Mrs. Smith, nice to see you. Look, you’re not having any problems taking those pills I told you to take, are you?” Now we’ve asked the question in such a way, the answer is definitely going to be, “Oh no, doctor, I’m fine with this.”

So we want to ask this in a different way by saying, for example, “You know, most people we know oftentimes forget or struggle around taking their medications. What’s it been like for you? How do you think about your meds?”

Scott, Susan, any other ideas about how you might approach that or what you might else say? Because it’s super important.

Scott Johnson: I love this question, this point. I don’t believe there’s any such thing as small change, right? And so when you’re introducing a new, whatever it is, into someone’s life, it takes some time to figure your way around that.

I think it’s important to check in and ask open-endedly, like, “How’s it going with that new adjustment we made? What are you experiencing?”

Open it up and see how that goes.

Susan Guzman: And to normalize that it’s hard for people, you know, it’s, “I’ve asked you to do a new behavior. It’s hard for a lot of people. How’s it going for you?” Like, make it an okay thing to bring up.

Bill Polonsky: And even if you’ve quit that medication I recommended to take, or you haven’t started it, I want to normalize that because, in fact, a lot of people feel so uncomfortable and so suspicious, they may not start. So I want to normalize that, but I want to keep talking about it because I’m probably still going to try and talk you into it.

So the second thing on the list is just forgetfulness because it is real. So again, there are things that we know that can address forgetfulness, and it’s those simple things that we’ve already mentioned earlier, like asking people to leave their pills next to their coffee pot or their toothbrush in the morning or by helping involve other people.

So again, some of those things I mentioned before that don’t work very well in large populations can make a difference if we’re focusing specifically on that population where it is forgetfulness and not other things behind forgetfulness.

Because we know that even people who say, oh yeah, I do forget my meds often. If you ask them more, they’re more likely to say, I’m not really sure they’re accomplishing anything anyway, or they’re kind of expensive. So there are other reasons often that we want to ask about and listen to respectfully.

I’m just gonna go on. Patient-provider trust. We know, as I mentioned earlier, how important trust is. This is a big topic for Susan and I, and probably the most difficult one to address really quickly.

I would say… When healthcare providers can become better listeners, when your patient knows that we’re on the same side and that simply you’re doing that by being a better listener, everything begins to change, everything.

And if you’re a busy healthcare provider and you have no time, you’re thinking, “Oh my God, you’ve got to be kidding me.” It doesn’t have to be half an hour of hanging out with your head at an angle and nodding with great empathy.

It means taking a few moments at the beginning of an encounter with any patient to say, “Mrs. Smith, it’s nice to see you. Can you tell me, you know, what’s been driving you nuts about diabetes? What’s been going on in your life?” Anything to treat that person not as a number, but as a human, begins to engage empathy and collaboration and trust. We know how important this is.

What do you guys think? Comments about either of those, Susan? Scott?

Scott Johnson: Yeah, I think that when I think about patient-provider trust, I also want to point out that we, as patients in that equation, have a responsibility to be responsible advocates for ourselves and maybe push outside our comfort zone a little bit and be brave enough to bring up things that we are struggling with or can’t figure out and not be afraid to open that discussion up.

I think that’s important too. At least some of that responsibility falls on us as patients.

Bill Polonsky: That’s a really good point. Like, “I’m uncomfortable with what you just recommended I take, doctor.” Right? Or something like that. It has to be two ways in that fashion.

Susan Guzman: I was just going to add in – this is kind of leading into the next point, which is about addressing or asking about beliefs, but that when you are listening, kind of have a sense of what you’re listening for.

I’m encouraging people to listen for the good reasons that they’re having a challenge with whatever you’re recommending. Like really listen for the good reasons–and they don’t have to be good reasons to you–but that you respect the fact that there are good reasons to them.

Bill Polonsky: And I guess I would just add, if you’re going to be able to listen to that, you have to ask about it, right?

Susan Guzman: Right.

Bill Polonsky:

So point four is to make sure that when you see an issue like this, you ask, how do you think about that pill or those medications I’ve prescribed? And specifically,

I like to get into details. What do you see? Susan, I hope I’m echoing what you’re saying. I’m going to ask people, how do you think about what the possible benefits are to that Metformin or that Ozempic, or whatever it is I recommended you take, and what do you see as the negatives? How do you think about those positives versus negatives? And having that kind of discussion can tell you so much about what’s really going on.

Am I getting at what you were saying, Susan?

Susan Guzman: Absolutely, yes.

Scott Johnson: I think points one and four are somewhat related, aren’t they?

Let’s say a family member starts a new medication, and they think that they’re experiencing side effects related to that new medication. being able to talk with the doctor to verify if that is true and find out if there are options or if that’s expected and what that path looks like?

Susan Guzman: Absolutely.

Bill Polonsky: We know that about 30% of all the prescribed medications in the market do have what’s called a black box warning. They potentially have quite significant and serious side effects, potentially.

And yet, all those medications are still prescribed. Well, what’s going on? Are these people evil who are prescribing this? Well, no. It’s that individual is prescribing it, that physician, whoever it might be, believes, as he’s recommending this medication for you to take. That the benefits, the pros, outweigh the potential negatives. And you as an individual patient may or may not agree with that, but it’s important to have that conversation because if you trust your physician, you might believe he actually knows enough to be making a reasonable recommendation.

And that’s why the last point in this slide, that’s why these points 1 through 5, are in this order. It’s only after doing 1 through 4 we want to be able to, again, respectfully offer new information.

First, We want to address the reasons why taking these medications might be necessary, it’s called perceived necessity, and that means talking about the pros. We meet people all the time and say, yeah, my doctor told me to take this stuff called Januvia or put me on insulin, but I don’t really know why I’m taking it, and I don’t know what it’s supposed to achieve.

And again, there’s been lots of studies showing that many people aren’t convinced that taking their medications are helping or accomplishing much because they can’t feel it.

So are we helping people believe that medications are potentially valuable and can accomplish something? And at the same time, we wanna talk about people’s perceived concerns.

So that people have told us about their suspicions about these meds. You know, “Well, my grandmother, you know, I remember a doctor put her on insulin, and all of a sudden, she began having trouble with her eyes and kidneys. And now you want me to take that stuff? I don’t know.”

We want to be able to talk about that. Well, you know, probably it wasn’t the insulin that did it to your grandmother. It was the fact that there had been no interventions to help her get on any medications for decades. That was an issue. That people have understandable concerns that are worthy of being discussed.

And we know we can address many if not most of them. And by the way, sometimes you can address these pros and cons together. And I’ll tell you my favorite way to do that.

One of my favorite examples is sometimes I’ll meet someone who says, “Well, you know my doctor. I’m new to diabetes, and they recommended I take metformin. But I don’t know. I don’t know. I’ve heard bad things about that stuff.”

I go, “Yeah, there are some significant side effects to metformin you should be aware of. Let me give you an example. There’s some recent evidence that one of the side effects is it may reduce your risk of developing certain types of cancer.”

And people go, “Wait a minute, that’s a side effect?” “Yeah, just thought you should know. There’s also some mixed evidence that it actually might reduce your risk for certain forms of dementia over the course of years.”

“Wait, but that would be a good thing, right?”

“Yeah!”

So there are ways of providing new perspectives and talking about, I think, medications to help people be concerned as they should always be.

We can empathize with the fact that most of us would prefer to be taking less or none, but to help them come to, with the right information, with the right evidence, and the right knowledge, come to good conclusions on their own.

And again, we think if we can help people with the right meds and stay with them, we know we’re helping them to get to a safer place with their diabetes.

So I’m going to shut up and let you guys talk now. What do you think about those last points regarding how we want to leave this with folks?

Scott Johnson: I enjoy all of these points. I think offering new information and education about the medications is really valuable.

It can be a little scary if we go off –we, as patients–go off and do our own research on these medications. There’s a lot of misinformation out there. There’s a lot of good information out there. And with that information, it should lead to a beneficial and informative discussion with your healthcare provider.

The point I want to make is don’t go read some scary side effect story and leave it at that. Bring that back, if you’ve bumped into that information, bring that back to your provider and have a conversation with them.

Bill Polonsky:

Exactly. Yeah.

Susan Guzman:

Very good point, Scott.

Bill Polonsky: Susan anything? How else would you want to conclude everything we’ve talked about? What else would you want to add?

Susan Guzman: I think just from a healthcare professional perspective, I think it’s very easy to forget to, you know, as the professional to forget to follow up on the medication.

Unless you’re in a system where you can see refill behavior, you may not even, it may not even occur to you to ask, like, I know for myself, I don’t really get asked about this.

What I hear is, do you need a refill? Not “How is it going?” You can learn a lot about how a person feels about their chronic health condition, in particular diabetes or high blood pressure, just by asking the question.

And as a mental health professional, and I’m working with someone who’s really struggling with their diabetes when I ask these questions, a lot of times I ask them just to bring their medicine in so we can talk about what they’re on and I can know.

Many times, people will show me their medicines–and they’ll go, “I don’t even know what this is or why I’m supposed to be taking it.” And there’s the problem right there. And sometimes these interventions are so easy.

I’m like, “Oh, well, that’s your blood pressure medication. And here’s why it’s important with diabetes.” And they’re like, “Oh, well, if I knew that, I’d have been taking it.”

To me, that’s really a bummer because that was a very simple intervention.

Scott Johnson: I also want to acknowledge a layer of overhead work involved in simply managing prescriptions.

Susan Guzman: Mm-hmm.

Scott Johnson: I don’t know about most people out there, but my prescriptions rarely run out at the same time, which means that if I go to a traditional pharmacy, I might be making three or four visits to a pharmacy every month and that’s a hassle and that’s just picking them up.

What about keeping track of when I need to request refills and which doctor does the refills? There are ways to systemize some of that stuff and help, but I want to acknowledge that layer of frustration as well.

Susan Guzman: Very good. Thank you, Scott.

Bill Polonsky: So we should probably wrap up. Of course, one of the reasons I think we should wrap up is because I actually need to go to the pharmacy and pick up some medications for myself.

Bill Polonsky:

But one of the other reasons is that we’ve gone on too long.

I hope this is gonna be helpful for those of you who are listening. Again, we think if we broach the subject with our patients, we think if we can help identify what we see as a very large problem all over this country, that people really struggle around taking the medications, but they do so for good reasons.

And that… by simply being good listeners and understanding and addressing those good reasons as opposed to just wagging our fingers at our patients or focusing on just forgetfulness, we think we can really help people do much better and live longer and healthier lives.

So, Scott, that’s all I really wanted to say. And Susan, I’m really glad you’re here. And we’ve spent so many years focusing on this subject. Normally we take a whole day when we meet with the healthcare providers to review everything we know about strategies for addressing this. So we’ve tried to do this as briefly as possible, but I’m glad we’ve had this opportunity. So thanks.

Susan Guzman: Thank you, Bill.

Scott Johnson: Yes. Thank both of you for digging into this sticky topic of taking our medications.

It’s clear that there’s a lot to learn, but that we’re making progress, but there’s still work yet to be done.

Also, big thanks to everyone watching. We appreciate you sharing your time with us. As always, I’m excited to share more in our next episode. We’ll see you then.